Chase Bergeson is an environmental scientist living in Raleigh, NC. She is passionate about working with communities on conservation of our water resources. She has an MS in Natural resources from NC State University and has experience working in water quality monitoring, environmental consulting, and environmental education. She loves to spend time with her friends and family, travel, swim, kayak, and walk in the woods.

White Pater: Importance of Marsh Migration Corridors

Abstract

Coastal tidal marshes are an important ecosystem in the Carolinas as they provide many essential resources and services to our coastal communities. The imminence of rising sea levels threatens to submerge marshes, which could negatively impact agriculture, drinking water, inland communities, and coastal ecosystems.

As climate changes, it will become critical to provide protected corridors through which coastal tidal marshes can migrate inland and continue to protect our coastlines. In the Carolinas, the creation of these corridors may require the aid of humans to remove man-made barriers (e.g., hardened shorelines), conserve and manage uplands, and collaborate with coastal communities and farmers to provide mutual social, economic, and environmental benefits for all.

Problem Statement

As our climate continues to warm over the coming decades, our sea levels will also rise. Many of our saltwater marshes are located on the Carolina coast, barely above current sea level. In fact, 1,729 square miles of the North Carolina coast is less than one meter above sea level (N.C. Interagency Leadership Team, 2010). As sea levels rise, these important wetlands will be vulnerable to inundation and transformation from coastal tidal marsh to open water. Human interventions, such as shorelines hardened with seawalls or bulkheads, berms, dikes, roads and even buildings could further prevent coastal tidal marshes from inland migration (Fuller, 2011). The loss of these wetlands will have negative impacts on coastal communities who rely on these wetlands as a buffer against wave action, flooding, and saltwater intrusion which can impact agriculture and harm infrastructure. It will also negatively affect the many types of flora and fauna that depend on these marshes for critical habitat.

Background

Coastal tidal marshes are non-forested wetlands occupied mostly by grasses and rushes (National Geographic, n.d.). They occur in both fresh and saltwater tidal areas. Coastal tidal marshes extend along hundreds of miles of coastline in the Carolinas (Nagy, 2015).

Coastal tidal marshes provide abundant services to humans and the environment. They help protect the shoreline from wave action and flood-causing storm surges. They help prevent saltwater intrusion, which in turn protects agricultural lands, drinking water supplies, and coastal communities. They also filter out terrestrial pollutants and lessen human impact on our oceans. Additionally, they provide habitat for many fish, birds, and other animals. (National Geographic, n.d.)

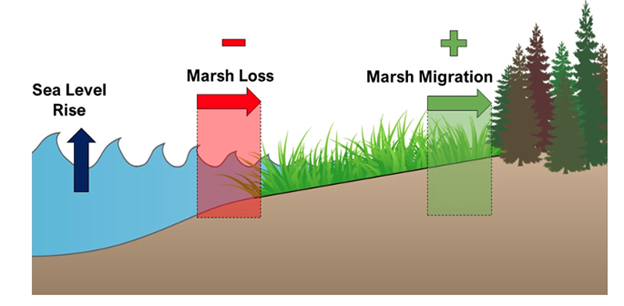

Coastal tidal marshes are abundant in the Carolinas but are threatened by human hydrologic management through ditching and channelization and activities that limit sediment flow to marshes such as upstream damming. They are also threatened by shoreline development that promotes the installation of bulkheads, seawalls, berms, and roads (Beever et al., 2012). Another major looming threat to coastal tidal marshes is sea level rise. To protect this important wetland type, marshes will need to be able to move inland to higher ground as sea levels rise. This is known as marsh migration and occurs not only in coastal tidal marshes, but to a lesser degree in inland freshwater marshes.

Coastal tidal marshes can “migrate” into adjacent uplands, through accretion of sediment which increases surface elevation and allows marshland to develop above continuously rising waters. If water level rises too quickly, current marshlands will become open water and too wet for marsh plants to survive (Fagherazzi et al., 2019). If the area inland of the marsh is unimpeded by man-made barriers, such as seawalls, and is high enough to bring the marsh close to or slightly above sea level, then with the right conditions, marsh flora may be able to shift inland. As storms inundate upland areas, upland soils will become saltier, causing die back of upland plants and creating conditions for marsh plants to grow (Fagherazzi et al., 2019). This form of “migration” can keep coastal tidal marshes from being lost altogether or can possibly even expand marshland area in some places. However, as marshes move inland, other ecosystems or land uses will be lost or transformed. This may mean a loss of arable agricultural land or forested areas which is already happening in the Carolinas (Martinez and Ardón, 2021, Holman 2022, Breisinger 2021, NOAA). Farmers in some low-lying areas have had increasing issues with saltwater intrusion from storm surges (Kaplan, 2019, CISA University of South Carolina, 2012). Forested freshwater swamps along tidal creeks and rivers have transitioned to tidal marshes full of dead or dying trees, named “ghost forests” due to their gray skeleton-like appearance (Martinez and Ardón, 2021; Holman, 2022; Breisinger, 2021).

Solutions

Some Carolina coastal tidal marshes are not able to naturally migrate due to man-made barriers or an inability to accrete sediment faster than rising sea levels. In other states natural barriers such as rocky outcrops and steep slopes may also impede marsh migration (Fuller et. al., 2011). Human intervention may aid migration through the creation of marsh migration corridors. Corridors consist of upland areas onto which marshes can slowly move upward as sea levels rise. These corridors require sufficient elevation for marshes to be higher than open water, a lack of physical barriers to migration, and a suitable natural landscape for marsh habitat to establish and thrive.

Humans can aid in the development of marsh migration corridors using the Resist-Accept-Direct (RAD) methodology (Shuurman et al., 2020). With this method, we can resist negative changes to our coastal system by avoiding the worst impacts of sea level rise, accept the inevitable inundation of some of our marshes, and direct the marshes’ inland migration by facilitating open corridors and conditions in which new marshland will thrive.

There are several projects along the Atlantic coast creating strategies for the creation of marsh migration corridors aimed at maintaining or increasing the total area of marshland in each area, especially as sea level rises. The scope of these projects varies from preservation of predicted natural migration corridors, to prioritization of locations for intentional marsh migration corridors, to implementation of public and private means of anthropogenically facilitating marsh migration in certain areas. The strategies suggested by these projects or related studies of marsh migration include physical alterations to the landscape, regulatory restrictions or incentive programs, and public/community outreach and involvement. Some of these strategies are highlighted below:

Identify Potential Corridors

One of the major areas of focus in marsh migration corridor research has been the identification and prioritization of potential corridors. Digital methods have included the use of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and modeling techniques to remotely determine which areas are most suitable for corridors (EPA, 2016). Assessments using these techniques may look for available land parcels adjacent to current marshes. They may also use elevation data and estimates of sea level rise to detect the most vulnerable areas of marshland in need of corridors. Other models will assess potential marsh habitat as a way of prioritizing marsh corridor locations. Many governmental and academic groups are using such models as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Habitat Priority Planner (NOAA Coastal Services Center, n.d.), the Salt Marsh Coastal Parcel Planning Tool (Road Island Salt Marsh Conservation Project n.d.), and the Sea Level Affecting Marshes Model (SLAMM) (Warren Pinnacle Consulting Inc., 2017). Additionally, the value of potential corridors to surrounding communities can play a big role in prioritizing corridors. If a current land use is more valuable to a community than a coastal tidal marsh, there may be resistance to a marsh migration corridor (Fagherazzi et al., 2019).

Coordinate with Local Communities and Stakeholders

Many studies have highlighted the great need to work with coastal communities and local organizations to make marsh migration a success. Local communities have their own needs and desires when it comes to marsh management. It is critical to involve the local community in shaping their own landscapes. Aligning environmental goals with community goals can help ensure the longevity of projects and avoid environmental injustices. Local communities and stakeholders have knowledge and resources that can contribute to mutually beneficial projects. They can also be important stewards of marsh migration corridors. Corridors can be created in ways that help uplift surrounding communities and fit in with their goals and needs. They can provide important ecosystem services to communities if community collaboration is obtained. Collaborating with communities in every step of the process is essential to successful projects (Van Dolah et al., 2020). A unique example of local collaboration in the coastal Carolinas is with the Gullah-Geechee community. This community is deeply knowledgeable about their local marshes and the threats that face them. They are currently part of a PEW Charitable Trust initiative to conserve a million acres of marsh. These lands are sacred to this community and thus working with the Gullah-Geechee is especially important (PEW, 2021a).

Transition Agriculture

Many coastal marshes in the Carolinas are bordered inland by agricultural fields. As sea levels rise, agricultural fields are becoming inundated with salt water, limiting the land available for farmers to grow the crops that they grew previously (Fagherazzi et al., 2019). However, there are opportunities for farmers to both protect their future finances and create space for inland marsh migration. Alternative future scenarios for farmers include, continuing current farming activities while maintaining a buffer of tidal marshland between agricultural land and open water or the planting of salt tolerant marsh crops (Lerner et al., 2013). These marshes can protect crops further inland by absorbing flooding events and preventing salt-water intrusion of cropland, allowing farmers to continue to farm some of their land as sea level rises. Another option is for farmers to transition from growing crops to aquaculture that is compatible with marshes (Andrews, 2020). With this option, the land could still be used for economic benefit, while simultaneously allowing for marsh migration. Working with farmers will be an essential component of any large-scale creation of marsh migration corridors in the Carolinas.

Conservation and Land Management

An essential component to creating migration corridors will be putting land into conservation easements and appropriately managing those easements to promote marsh migration (Fagherazzi et al., 2019). Funding for the purchase of easements could come from The Federal Land and Water Conservation Fund, the Wetlands Reserve Program, and local land trusts, among others (Lerner et al., 2013). Some of the best practices for managing the areas upland of current marshes is to remove dead trees, invasive species, and man-made barriers that may impede migration (Beever et al., 2012; Lerner et al., 2013; University of Rhode Island, n.d.; Andrews, 2020). Dead trees left standing in transitioning forest lands inland of these marshes may limit salt marsh bird nesting habitat (Lerner et al., 2013) and even contribute to greenhouse gas emissions, by assisting the release of methane from soils (Martinez and Ardón, 2021). Hydrology and topography must also be managed so that water flows bring a steady supply of sediment to marshes (Beever et al., 2012: University of Rhode Island, n.d.). This is especially important for salt marshes that may become sediment starved (Moorman, 2021). Other management strategies have included increasing surface area elevation and reducing interior ponding (Lerner et al., 2013) and back-filling man-made pits and ditches (Beever et al., 2012).

Regulatory Action

Many communities are turning to regulatory action to protect the future of their coastal wetlands. Regulatory actions or governmental incentives have been used all along the Atlantic coastline to curb coastal development practices. Some innovative policies have included laws and regulations making living shorelines standard practice in coastal Virginia (Andrews, 2020). Living shorelines are protected and stabilized shorelines made from natural materials such as plants, sand, and rocks. The use un-hardened living shorelines, devoid of rip rap (Beever et al., 2012), can help create a transition zone for landward moving marshes. There have also been several communities in which the new development of hardened coastal surfaces more generally has been limited (Van Dolah et al., 2020; Andrews, 2020).

There are also communities in which developers are given incentives to place ideal migration corridor land in easements, in order to be rewarded with permits issued for denser development in other locations (Andrews, 2020). In areas where flooding affects homes, there are state and federal programs that can be used to voluntarily buy back land from homeowners and create easements from those tracts of land. As sea levels rise and coastal flooding worsens, these programs may be an avenue for converting developed land into corridors. However, it should be noted that the uprooting of communities in this way and the inequities associated with many communities that are adversely affected by flooding brings with it issues of environmental justice that must simultaneously be considered and addressed.

Carbon Markets

Another creative idea is the use of carbon markets and nutrient reduction incentives to encourage the protection of coastal marshes and private contributions to marsh migration corridors in order to meet project requirements or obtain pollution credits (RI Salt Marsh Conservation Project, n.d.).

Specific strategies especially for working with farmers and the communities along with details behind these strategies can be found in the resources in the Reference section.

Conclusions

Protecting the coastal marshes of the Carolinas will be a major challenge in the coming decades, but with forethought, planning, and the cooperation of diverse stakeholders across the region there is a positive outlook for the future of these wetlands. We have the tools and knowledge necessary to successfully create marsh migration corridors through which marshes can move inland. With adequate funding, resources, and local community involvement these corridors can become a reality. The PEW Charitable Trust and the Southeast Regional Partnership for Planning and Sustainability are already working on such large-scale projects (PEW, 2021b). Successful projects in the Chesapeake Bay Region (Lerner et al., 2013) can serve as models going forward. As sea levels rise, managed marsh migration corridors will be critical for the protection of this valuable Carolina wetland resource.

Meet the Author

References

Andrews, E.A. Legal and Policy Challenges for Future Marsh Preservation in the Chesapeake Bay Region. Wetlands 40, 1777–1788 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-020-01389-z

Beever, L. B., Gray, W., Cobb, D., & Walker, T. (2012). Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment and Adaptation Opportunities for Salt Marsh Types in Southwest Florida. The Charlotte Harbor National Estuary Program.

Breisinger, H. (2021). North Carolina’s shoreline estuaries are transforming into “ghost forests,” by why? WHQR Public Media. https://www.whqr.org/local/2021-06-03/north-carolinas-shoreline-estuaries-are-transforming-into-ghost-forests-but-why

Carolina Integrated Sciences and Assessments, University of South Carolina. 2012. Assessing the Impact of Saltwater Intrusion in the Carolinas under Future Climatic and Sea Level Conditions. https://cpo.noaa.gov/sites/cpo/Projects/RISA/2013/reports/2012_CISAandSCSeaGrant_SalinitySARPReport.pdf

EPA. (2016, April 14). Maryland Analyzes Coastal Wetlands Susceptibility to Climate Change (District of Columbia) [Overviews and Factsheets]. https://www.epa.gov/arc-x/maryland-analyzes-coastal-wetlands-susceptibility-climate-change

Fagherazzi, Sergio, et al. “Sea Level Rise and the Dynamics of the Marsh-Upland Boundary.” Frontiers Environmental Science, vol. 7, 2019, https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fenvs.2019.00025.

Fuller, Roger, et al. Marshes on the Move. The Nature Conservancy Global Marine Team and NOAA National Ocean Service Coastal Services Center, Oct. 2011.

Guimond, J. A., & Michael, H. A. (2021). Effects of marsh migration on flooding, saltwater intrusion, and crop yield in coastal agricultural land subject to storm surge inundation. Water Resources Research, 57, e2020WR028326. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020WR028326

Habitat Priority Planner: Marsh Migration. (n.d.). NOAA Coastal Services Center. Retrieved November 3, 2021, from https://coast.noaa.gov/data/digitalcoast/pdf/hpp-applications-marsh-migration.pdf

Holman, V. 2022. Ghost Whisperers. Salt Magazine. http://www.saltmagazinenc.com/ghost-whisperers/.

Kaplan, S. (2019, March 1). Ruined crops, salty soil: How rising seas are poisoning North Carolina’s farmland. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/ruined-crops-salty-soil-how-rising-seas-are-poisoning-north-carolinas-farmland/2019/03/01/2e26b83e-28ce-11e9-8eef-0d74f4bf0295_story.html

Kozak, C. (2019, December 10). Currituck Marsh Focus for Resilience Project. CoastalReview.org. https://coastalreview.org/2019/12/currituck-marsh-focus-for-resilience-project/

Kottler, Ezra. “Sea-Level Rise, Marsh Migration, and Coastal Resilience.” Wetland Restorations, 22 Mar. 2021, https://wmap.blogs.delaware.gov/2021/03/22/sea-level-rise-marsh-migration-and-coastal-resilience/.

Ladin and Moorman, 2021, USFWS, Southeast Region SET Analysis, https://ecos.fws.gov/ServCat/DownloadFile/199786

Lerner, J.A., Curson, D.R., Whitbeck, M. and Meyers, E.J., Blackwater. 2100: A strategy for salt marsh persistence in an era of climate change, 2013, The Conservation Fund (Arlington, VA) and Audubon MD-DC (Baltimore, MD).

Martinez, M., Ardón, M. Drivers of greenhouse gas emissions from standing dead trees in ghost forests. Biogeochemistry 154, 471–488 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-021-00797-5

Moorman, M. (2021, September 26). Will the Marsh Stay or Will It Go? Coastal Wetland Transformations in the South Atlantic Basin.

Nagy, R. (2015). Moving Through the Marsh. Coastwatch, Winter 2015. https://ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/previous-issues/2015-2/winter-2015/moving-through-the-marsh/

National Geographic. (n.d.). Marsh. National Geographic Resource Library. Retrieved November 3, 2021, from https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/marsh/

NC Interagency Leadership Team. 2010. Climate maps. Maps produced by Renci (Renaissance Computing Institute) and UNC Asheville’s NEMAC (National Environmental Modeling and Analysis Center) http://www.climatechange.nc.gov/Climate_Maps_NC.pdf

PEW. (2021a). African Descendants Have Stake in Saving U.S. Southeast Salt Marshes. https://pew.org/3hvVEjm

PEW. (2021b). How Southeast Stakeholders Are Safeguarding Salt Marshes. https://pew.org/3qZyQLH

RI Salt Marsh Conservation Project. (n.d.). The University of Rhode Island Environmental Data Center. Retrieved November 3, 2021, from https://www.edc.uri.edu/ri-salt-marsh-conservation-project/

Schuurman, G., Cat, H.-H., Cole, D., Lawrence, D., Morton, J., Magness, D., Cravens, A., Covington, S., O’Malley, R., & Fisichelli, N. (2020). Resist-Accept-Direct (RAD)—A Framework for the 21st-century Natural Resource Manager. National Park Service. https://doi.org/10.36967/nrr-2283597

Van Dolah, E.R., Miller Hesed, C.D. & Paolisso, M.J. Marsh Migration, Climate Change, and Coastal Resilience: Human Dimensions Considerations for a Fair Path Forward. Wetlands 40, 1751–1764 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-020-01388-0

Warren Pinnacle Consulting, Inc. (2017). SLAMM: Sea Level Affecting Marshes Model. http://warrenpinnacle.com/prof/SLAMM/index.html