Importance of Small Wetlands

Abstract

Wetlands occur throughout North Carolina in variable sizes and landscape positions. How wetlands are protected and regulated changes over time based on the definition of a jurisdictional wetland. Impacts to federal and state jurisdictional wetlands resulting in loss are regulated by the United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) and North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (NCDEQ), respectively. Depending on the type of impact activities and permitting thresholds, impacts to jurisdictional wetlands may require a permit. Currently, wetlands that are not adjacent to or lack a hydrologic surface connection with a relatively permanent water, often referred to as geographically isolated wetlands, are not considered federally jurisdictional. In North Carolina, isolated wetlands have higher state permitting thresholds than federal jurisdictional wetlands. When a permit is required, impacts to wetlands must be avoided and minimized, as practicable. Because wetland regulations are focused on hydrologic connectivity and the size (or amount) of impacts, some small wetlands may be lost without requiring permitting and avoidance and minimization measures if total impacts for a proposed project are under the permitting threshold. Because the size of a wetland is not a direct indicator of how well the ecosystem is functioning or the value it has to the surrounding environment, other criteria based on the benefits a wetland can provide need to be incorporated into wetland regulations.1 Small wetlands provide benefits such as flood storage, water quality improvement, recreational opportunities, economic growth, public health, and increased biodiversity, and therefore should be protected. A landscape approach to regulate wetlands can be used to avoid and minimize impacts to wetlands that have the potential to provide the most environmental, economic, and community benefits.

Problem Statement: Loss of Small Wetlands

Due to development and other human activities that have resulted in land-use changes, a substantial amount of wetlands have been lost in the United States. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) estimates that approximately 220 million acres of wetlands once existed in the lower 48 states.2 By 1984, it is estimated that 54% of those wetlands were drained or filled; most wetlands were drained for crop production.3,4

In North Carolina, approximately half of all wetlands were lost by the mid-1980s, with the amount of wetlands reduced from approximately 11 million acres to around 4 million acres.5 For example, mountain bogs, a rare wetland type endemic to western North Carolina, have been estimated to cover over 5,000 acres in the past, but now only cover approximately 500 acres.6 Pocosins, a wetland type that occurs in eastern North Carolina also known as swamp-on-a-hill, once covered approximately 2.47 million acres; it has been estimated 33% of these wetlands have been destroyed.4 Many Carolina bays, a unique basin wetland habitat also found in eastern North Carolina, have been lost due to draining and converting land for agriculture and other uses.7 Because small wetlands are underrepresented in wetland inventories and mapping resources, the actual loss is difficult to assess.5 For this report, small wetlands are defined as being less than an acre in size.

Small wetlands are a vital environmental resource that provide a wide variety of benefits to humans and should be protected; however, the level of protection provided by federal and state regulations varies based on the size, location, and surface water connection of a wetland. The importance of small wetlands is often misunderstood and therefore overlooked when establishing permitting thresholds. Small wetlands are often viewed as less valuable than larger wetlands based on false assumptions that small wetlands have shorter hydroperiods, support fewer species, and the species found in small wetlands also inhabit larger wetlands.1 The destruction of small wetlands can lead to issues such as decreased water quality, increased flooding, a decline in biodiversity, and economic losses.3 As discussed in this paper, the value of small wetlands needs to be better understood to promote their protection.

Background: Small Wetlands in North Carolina

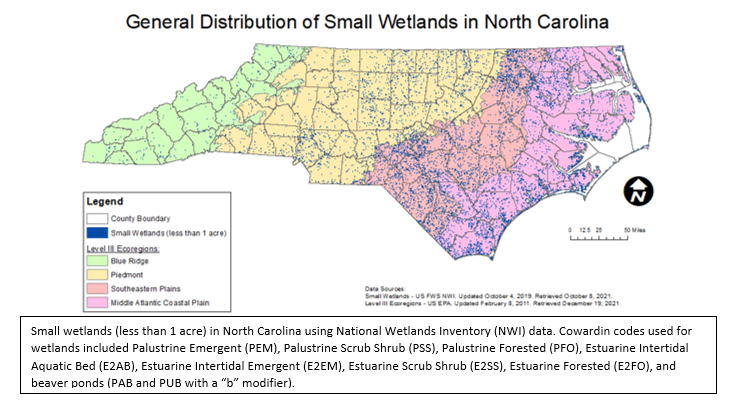

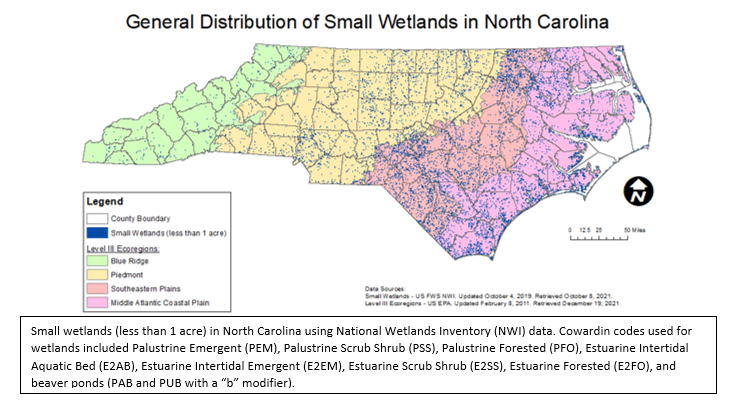

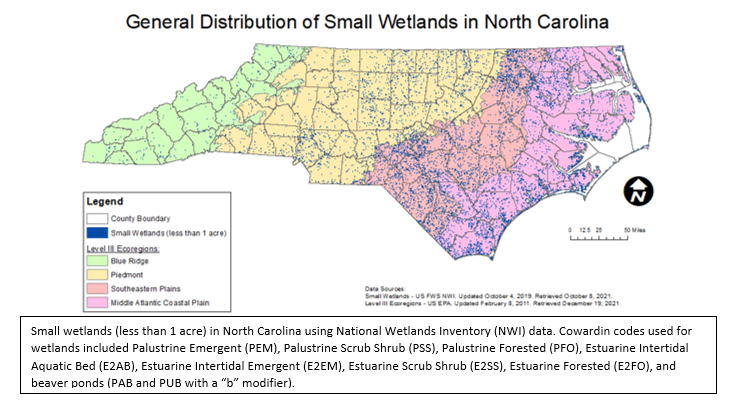

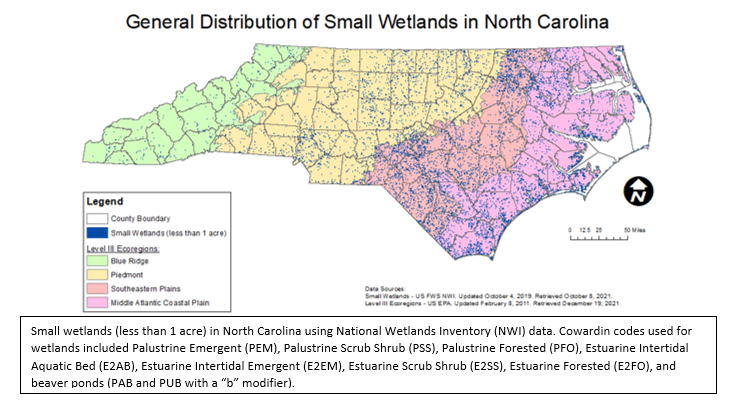

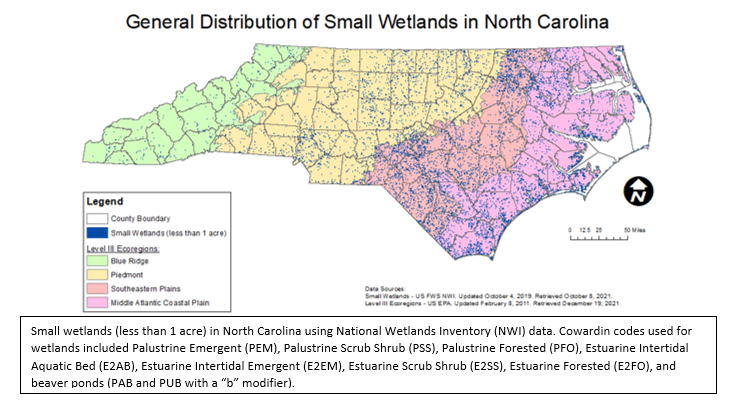

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines wetlands as “areas where water covers the soil or is present either at or near the surface of the soil all year or for varying periods during the year, including during the growing season.”8 They are often identified by their hydric soils, hydrophytic vegetation, and seasonally or permanently saturated soil within one foot below the ground surface. Depending on the wetland type, the hydrology of small wetlands ranges from standing water for much of the year to saturated soil just below the surface for a few weeks. Small wetlands occur across North Carolina ecoregions in varying landscape positions and proportions (Figure 1).

Figure 1. General Distribution of Small Wetlands in North Carolina (9,11)

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines wetlands as “areas where water covers the soil or is present either at or near the surface of the soil all year or for varying periods during the year, including during the growing season.”8 They are often identified by their hydric soils, hydrophytic vegetation, and seasonally or permanently saturated soil within one foot below the ground surface. Depending on the wetland type, the hydrology of small wetlands ranges from standing water for much of the year to saturated soil just below the surface for a few weeks. Small wetlands occur across North Carolina ecoregions in varying landscape positions and proportions (Figure 1).

Figure 1. General Distribution of Small Wetlands in North Carolina (9,11)

Abstract

Wetlands occur throughout North Carolina in variable sizes and landscape positions. How wetlands are protected and regulated changes over time based on the definition of a jurisdictional wetland. Impacts to federal and state jurisdictional wetlands resulting in loss are regulated by the United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) and North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (NCDEQ), respectively. Depending on the type of impact activities and permitting thresholds, impacts to jurisdictional wetlands may require a permit. Currently, wetlands that are not adjacent to or lack a hydrologic surface connection with a relatively permanent water, often referred to as geographically isolated wetlands, are not considered federally jurisdictional. In North Carolina, isolated wetlands have higher state permitting thresholds than federal jurisdictional wetlands. When a permit is required, impacts to wetlands must be avoided and minimized, as practicable. Because wetland regulations are focused on hydrologic connectivity and the size (or amount) of impacts, some small wetlands may be lost without requiring permitting and avoidance and minimization measures if total impacts for a proposed project are under the permitting threshold. Because the size of a wetland is not a direct indicator of how well the ecosystem is functioning or the value it has to the surrounding environment, other criteria based on the benefits a wetland can provide need to be incorporated into wetland regulations [1]. Small wetlands provide benefits such as flood storage, water quality improvement, recreational opportunities, economic growth, public health, and increased biodiversity, and therefore should be protected. A landscape approach to regulate wetlands can be used to avoid and minimize impacts to wetlands that have the potential to provide the most environmental, economic, and community benefits.

Problem Statement: Loss of Small Wetlands

Due to development and other human activities that have resulted in land-use changes, a substantial amount of wetlands have been lost in the United States. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) estimates that approximately 220 million acres of wetlands once existed in the lower 48 states.[2] By 1984, it is estimated that 54% of those wetlands were drained or filled; most wetlands were drained for crop production. [3,4]

In North Carolina, approximately half of all wetlands were lost by the mid-1980s, with the amount of wetlands reduced from approximately 11 million acres to around 4 million acres.[5] For example, mountain bogs, a rare wetland type endemic to western North Carolina, have been estimated to cover over 5,000 acres in the past, but now only cover approximately 500 acres.[6] Pocosins, a wetland type that occurs in eastern North Carolina also known as swamp-on-a-hill, once covered approximately 2.47 million acres; it has been estimated 33% of these wetlands have been destroyed.[4] Many Carolina bays, a unique basin wetland habitat also found in eastern North Carolina, have been lost due to draining and converting land for agriculture and other uses.[7] Because small wetlands are underrepresented in wetland inventories and mapping resources, the actual loss is difficult to assess.[5] For this report, small wetlands are defined as being less than an acre in size.

Small wetlands are a vital environmental resource that provide a wide variety of benefits to humans and should be protected; however, the level of protection provided by federal and state regulations varies based on the size, location, and surface water connection of a wetland. The importance of small wetlands is often misunderstood and therefore overlooked when establishing permitting thresholds. Small wetlands are often viewed as less valuable than larger wetlands based on false assumptions that small wetlands have shorter hydroperiods, support fewer species, and the species found in small wetlands also inhabit larger wetlands.[1] The destruction of small wetlands can lead to issues such as decreased water quality, increased flooding, a decline in biodiversity, and economic losses.[3] As discussed in this paper, the value of small wetlands needs to be better understood to promote their protection.

Background: Small Wetlands in North Carolina

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines wetlands as “areas where water covers the soil or is present either at or near the surface of the soil all year or for varying periods during the year, including during the growing season.”8 They are often identified by their hydric soils, hydrophytic vegetation, and seasonally or permanently saturated soil within one foot below the ground surface. Depending on the wetland type, the hydrology of small wetlands ranges from standing water for much of the year to saturated soil just below the surface for a few weeks. Small wetlands occur across North Carolina ecoregions in varying landscape positions and proportions (Figure 1).

Figure 1. General Distribution of Small Wetlands in North Carolina (9,11)

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines wetlands as “areas where water covers the soil or is present either at or near the surface of the soil all year or for varying periods during the year, including during the growing season.”[8] They are often identified by their hydric soils, hydrophytic vegetation, and seasonally or permanently saturated soil within one foot below the ground surface. Depending on the wetland type, the hydrology of small wetlands ranges from standing water for much of the year to saturated soil just below the surface for a few weeks. Small wetlands occur across North Carolina ecoregions in varying landscape positions and proportions (Figure 1).

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines wetlands as “areas where water covers the soil or is present either at or near the surface of the soil all year or for varying periods during the year, including during the growing season.”8 They are often identified by their hydric soils, hydrophytic vegetation, and seasonally or permanently saturated soil within one foot below the ground surface. Depending on the wetland type, the hydrology of small wetlands ranges from standing water for much of the year to saturated soil just below the surface for a few weeks. Small wetlands occur across North Carolina ecoregions in varying landscape positions and proportions (Figure 1).

Figure 1. General Distribution of Small Wetlands in North Carolina (9,11)

Figure 1. General Distribution of Small Wetlands in North Carolina (9,11)

The state of North Carolina is typically described using three physiographic provinces: Mountains, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain. These provinces are divided using Level III ecoregions boundaries (Figure 1).[9] Ecoregions are areas with distinctive ecological and geographical characteristics including landscape, land surface form, geology, soils, climate, and natural plant communities.[10] In North Carolina, the Blue Ridge ecoregion contains the Mountains province and is the farthest inland ecoregion of the state. The Piedmont ecoregion contains the Piedmont province and is located between the Blue Ridge escarpment bordering the Mountains and the fall line bordering the Southeastern Plains ecoregion. The Coastal Plain province consists of the Southeastern Plains and Middle Atlantic Coastal Plain ecoregions.

The National Wetlands Inventory (NWI) is a digitized map that provides general information about potential wetland areas, but it is not a reliable source for identifying all small wetlands. The NWI was created using aerial imagery primarily from the 1980s and involved a minimum mapping size of 0.5 acre, meaning wetlands smaller than 0.5 acre were often not included in the NWI.5 Wetlands that could not be detected using aerial photography were also not included in the NWI. Recent studies from the North Carolina Division of Water Resources (DWR) have shown that the NWI excludes many small wetlands, particularly in the Mountains and western Piedmont.[5] Because the NWI “is the only widely available map of wetland locations and extent within [North Carolina],” it is often used for natural resources management and project planning; however, the NWI was not intended to be used for such purposes.5 Accurate representation of small wetlands in readily available mapping resources would allow for the selection of projects and site locations that avoid and minimize impacts to small wetlands earlier in the project planning process.

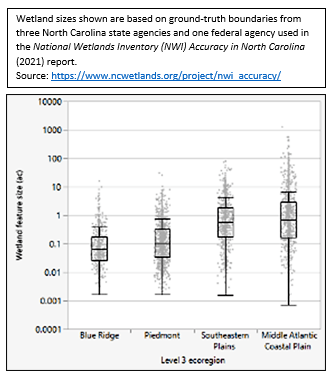

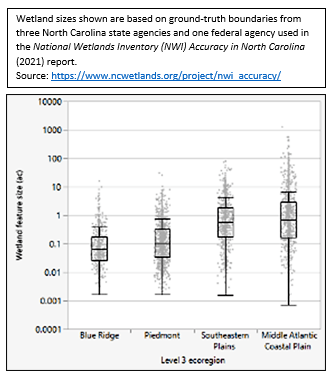

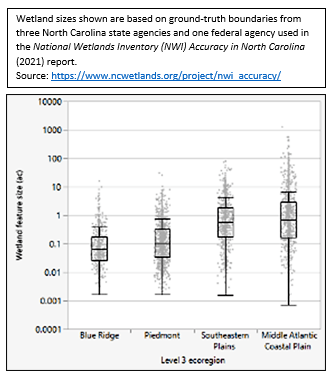

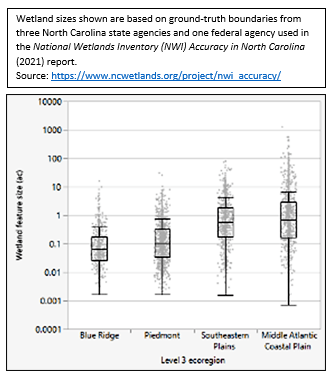

Although there is not an accurate, comprehensive map of all wetlands across North Carolina, there are some known facts about the distribution and size of wetlands. The Mountains province has the least amount of wetlands compared to the other provinces of North Carolina (Figure 1). These wetlands are often small and occur in flat areas where surface water collects and groundwater discharges (Figure 2).12 The Piedmont contains more wetlands than the Mountains, but most wetlands are also typically small.5 Most of the wetlands in North Carolina are located in the Coastal Plain and tend to be larger than wetlands in the Mountains and Piedmont provinces.5

Figure 2. North Carolina Wetland Size Distribution by Ecoregion (13)

Although there is not an accurate, comprehensive map of all wetlands across North Carolina, there are some known facts about the distribution and size of wetlands. The Mountains province has the least amount of wetlands compared to the other provinces of North Carolina (Figure 1). These wetlands are often small and occur in flat areas where surface water collects and groundwater discharges (Figure 2).[12] The Piedmont contains more wetlands than the Mountains, but most wetlands are also typically small.[5] Most of the wetlands in North Carolina are located in the Coastal Plain and tend to be larger than wetlands in the Mountains and Piedmont provinces.5

Figure 2. North Carolina Wetland Size Distribution by Ecoregion (13)

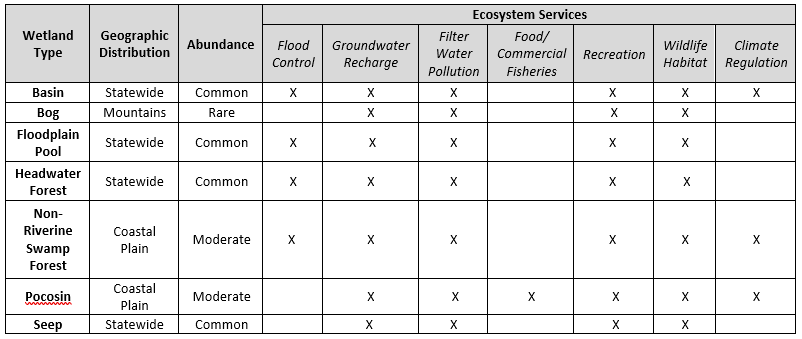

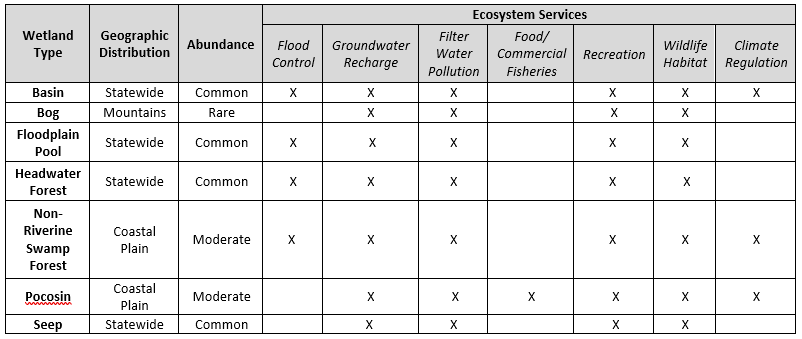

North Carolina hosts a variety of wetlands that can be categorized into general wetland types using the NC Wetland Assessment Method (NCWAM) based on where they occur on the landscape and the functions they perform.[14] All wetland types can vary in size; however, seven NCWAM wetland types are common types for small wetlands (Table 1). Each wetland type provides multiple ecosystem services that benefit humans and the environment, with recreation, wildlife habitat, groundwater recharge, and water quality filtration common to all small wetland types.

Table 1. Common NCWAM wetland types for small wetlands in North Carolina.

Flood Storage Benefits

An increase in the intensity and frequency of storms and heavy downpour events in recent years has led to more flooding in North Carolina.[15] Property damage in North Carolina related to hurricanes was estimated at $500,000 from 1970 to 1980 (equivalent to approximately $3.5 million today due to inflation) compared to $367 million from 2010 to 2020.[16,17] According to the 2020 North Carolina Climate Science Report, it is “very likely that extreme precipitation frequency and intensity” will continue to increase over the next century and “likely that increases in extreme precipitation will lead to increases in inland flooding.”[18] Because of wetland loss and degradation, flood damages from extreme precipitation events tend to be higher and more costly than if more properly functioning wetlands existed in various positions across the landscape.

Photo: NC Department of Transportation. 2021 (21).

The state of North Carolina is typically described using three physiographic provinces: Mountains, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain. These provinces are divided using Level III ecoregions boundaries (Figure 1).9 Ecoregions are areas with distinctive ecological and geographical characteristics including landscape, land surface form, geology, soils, climate, and natural plant communities.10 In North Carolina, the Blue Ridge ecoregion contains the Mountains province and is the farthest inland ecoregion of the state. The Piedmont ecoregion contains the Piedmont province and is located between the Blue Ridge escarpment bordering the Mountains and the fall line bordering the Southeastern Plains ecoregion. The Coastal Plain province consists of the Southeastern Plains and Middle Atlantic Coastal Plain ecoregions.

The National Wetlands Inventory (NWI) is a digitized map that provides general information about potential wetland areas, but it is not a reliable source for identifying all small wetlands. The NWI was created using aerial imagery primarily from the 1980s and involved a minimum mapping size of 0.5 acre, meaning wetlands smaller than 0.5 acre were often not included in the NWI.5 Wetlands that could not be detected using aerial photography were also not included in the NWI. Recent studies from the North Carolina Division of Water Resources (DWR) have shown that the NWI excludes many small wetlands, particularly in the Mountains and western Piedmont.5 Because the NWI “is the only widely available map of wetland locations and extent within [North Carolina],” it is often used for natural resources management and project planning; however, the NWI was not intended to be used for such purposes.5 Accurate representation of small wetlands in readily available mapping resources would allow for the selection of projects and site locations that avoid and minimize impacts to small wetlands earlier in the project planning process.

Although there is not an accurate, comprehensive map of all wetlands across North Carolina, there are some known facts about the distribution and size of wetlands. The Mountains province has the least amount of wetlands compared to the other provinces of North Carolina (Figure 1). These wetlands are often small and occur in flat areas where surface water collects and groundwater discharges (Figure 2).12 The Piedmont contains more wetlands than the Mountains, but most wetlands are also typically small.5 Most of the wetlands in North Carolina are located in the Coastal Plain and tend to be larger than wetlands in the Mountains and Piedmont provinces.5

Figure 2. North Carolina Wetland Size Distribution by Ecoregion (13)

Although there is not an accurate, comprehensive map of all wetlands across North Carolina, there are some known facts about the distribution and size of wetlands. The Mountains province has the least amount of wetlands compared to the other provinces of North Carolina (Figure 1). These wetlands are often small and occur in flat areas where surface water collects and groundwater discharges (Figure 2).12 The Piedmont contains more wetlands than the Mountains, but most wetlands are also typically small.5 Most of the wetlands in North Carolina are located in the Coastal Plain and tend to be larger than wetlands in the Mountains and Piedmont provinces.5

Figure 2. North Carolina Wetland Size Distribution by Ecoregion (13)

North Carolina hosts a variety of wetlands that can be categorized into general wetland types using the NC Wetland Assessment Method (NCWAM) based on where they occur on the landscape and the functions they perform.14 All wetland types can vary in size; however, seven NCWAM wetland types are common types for small wetlands (Table 1). Each wetland type provides multiple ecosystem services that benefit humans and the environment, with recreation, wildlife habitat, groundwater recharge, and water quality filtration common to all small wetland types.

Table 1. Common NCWAM wetland types for small wetlands in North Carolina.

Flood Storage Benefits

An increase in the intensity and frequency of storms and heavy downpour events in recent years has led to more flooding in North Carolina.15 Property damage in North Carolina related to hurricanes was estimated at $500,000 from 1970 to 1980 (equivalent to approximately $3.5 million today due to inflation) compared to $367 million from 2010 to 2020.16,17 According to the 2020 North Carolina Climate Science Report, it is “very likely that extreme precipitation frequency and intensity” will continue to increase over the next century and “likely that increases in extreme precipitation will lead to increases in inland flooding.”18 Because of wetland loss and degradation, flood damages from extreme precipitation events tend to be higher and more costly than if more properly functioning wetlands existed in various positions across the landscape.

Photo: NC Department of Transportation. 2021 (21).

Wetlands can store precipitation and slowly release it over time, which reduces stormwater runoff and lessens flash flood damage both locally and downstream. Furthermore, wetlands reduce the number of severe overbank flooding events by holding and storing significant amounts of floodwater from overflowing streams.[19] The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that one acre of wetland can store up to 1.5 million gallons of water.[19] Studies have shown that small, isolated wetlands have higher rates of evapotranspiration (evaporation of water and plants soaking up water and releasing it into the atmosphere) than larger bodies of water, indicating that smaller wetlands can reduce stormwater runoff more efficiently than larger ones.[20] The water absorbed in the wetland soils helps replenish water levels in streams and reduces drought on land during dry periods. As temperatures rise over the next century, “[i]t is likely that future severe droughts…will be more frequent and intense.”[18] Having wetlands dispersed throughout a watershed (an area where all water drains across the landscape to one common point) is crucial to minimize drought impacts. In coastal areas, small wetlands can reduce saltwater intrusion through groundwater recharge which helps protect freshwater wetlands from negative impacts such as tree mortality that may result from increased salinity levels by maintaining the water table levels at about sea level.[20] Protecting coastal freshwater wetlands reduces flood damages from storm surge.

Water Quality Benefits

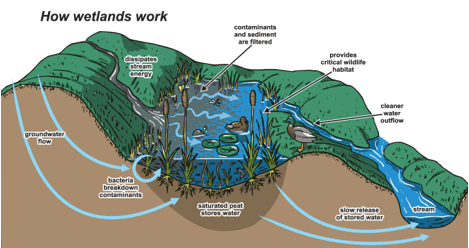

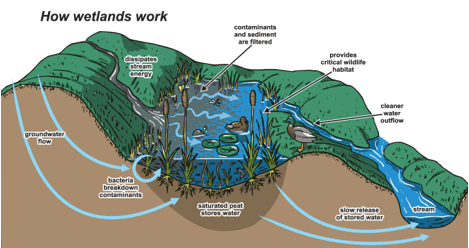

A common misconception is that small wetlands are isolated and therefore do not provide important hydrological and water quality benefits. All wetlands, small and large, are part of the larger surrounding watershed and can influence other ecosystems within the watershed. Evapotranspiration is an important ecosystem service provided by small wetlands that stabilizes the health of the surrounding watershed by reducing excess stormwater runoff that can carry harmful contaminants, excess nutrients, and sediment that impair water quality (Figure 3). For example, when analyzing the same rainfall event, “one inch of rain on an acre of woods produces little to no stormwater runoff” while “one inch of rain on an acre of asphalt produces 27,000 gallons of stormwater runoff that contains a variety of pollutants and causes widespread erosion.”[22] Small wetland vegetation and microtopography on the soil surface improve water quality by slowing the movement of water downslope and allowing for sediment to settle out, bacteria to breakdown contaminants, and excess nutrients to be taken up by plants and microorganisms, thus improving water quality. The wetland’s “natural filtration process makes water cleaner for drinking, swimming, and provides habitat for plants and animals.”[19]

Figure 3. How wetlands work and their role in water quality and ecosystem health (23).

Recreational Benefits

In 2016, 103.7 million Americans spent $156.9 billion participating in recreational activities such as hunting; fishing; and observing, feeding, and photographing wildlife in natural areas (Figure 4).[24] The 2011 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation report for North Carolina showed a total of $3.3 billion was spent on recreational activities related to wildlife that included $525 million for hunting, $1.5 billion spent for fishing, and $930 million spent for wildlife-watching.[25] People visiting small wetlands to hunt, fish, and observe wildlife can boost local economies, especially in rural areas, by spending money on and requiring services for transportation, lodging, food, beverages, equipment, licenses, permits, memberships, and/or land leases.

Figure 4. Wildlife-dependent recreational activities (26).

In a public input survey conducted in 2014 by the North Carolina Division of Parks and Recreation (DPR), most respondents (81%) believe it is “extremely or somewhat important to spend public funds to acquire land and develop outdoor state parks and recreation areas in North Carolina” but many indicated that a lack of time (59%) or a lack of available facilities (23%) are barriers to their participation in outdoor recreation.[27] Preserving small wetlands and adding amenities such as walking trails in urban and residential areas makes outdoor recreation activities more accessible. This would also improve nearby property values and promote healthier lifestyles, including physical and mental health.[28] The economic benefit gained from recreational activities heavily depends on the presence and health of local wetlands.

Biodiversity Benefits

Wetlands host a variety of plant and animal species, including approximately 70% of rare or endangered species in North Carolina that require wetlands to survive.[29] In the Mountains and western Piedmont, small wetlands provide habitat for over 90 rare, threatened, or endangered plant and animal species.[30] Mountain bogs are typically small and are among the rarest, most vulnerable habitats in the United States. These wetlands are the only or primary habitat for wildlife species such as the southern bog lemming (Synaptomys cooperi), a type of small mammal, the bog turtle (Glyptemys muhlenbergii), and plants species including swamp pink (Helonias bullata), mountain sweet pitcher plant (Sarracenia rubra), and bunched arrowhead (Sagittaria fasciculata).[30,12] Without mountain bogs, these species, along with many others, would not be able to survive. These species are adapted to wetlands without the high velocities of water that stream floodplain wetlands experience.

On January 13, 2022, the Center for Biological Diversity filed a petition to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) “to protect the southern population of the bog turtle as a federal endangered species in Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Georgia” and request the establishment of designated critical habitat.[32] There are currently only 10 sites with viable bog turtle populations (at least 40 individuals) in North Carolina.[32] Almost all the individuals found at these sites were adults, meaning there are very few young turtles to replace the adults and continue the survival of the species.[32] By listing the bog turtle as a federal endangered species and designating critical habitat, protection would be provided under the Endangered Species Act for mountain bogs that are used by existing populations.

Photo: The Appalachian Voice. 2014 (31).

Wetlands can store precipitation and slowly release it over time, which reduces stormwater runoff and lessens flash flood damage both locally and downstream. Furthermore, wetlands reduce the number of severe overbank flooding events by holding and storing significant amounts of floodwater from overflowing streams.19 The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that one acre of wetland can store up to 1.5 million gallons of water.19 Studies have shown that small, isolated wetlands have higher rates of evapotranspiration (evaporation of water and plants soaking up water and releasing it into the atmosphere) than larger bodies of water, indicating that smaller wetlands can reduce stormwater runoff more efficiently than larger ones.20 The water absorbed in the wetland soils helps replenish water levels in streams and reduces drought on land during dry periods. As temperatures rise over the next century, “[i]t is likely that future severe droughts…will be more frequent and intense.”18 Having wetlands dispersed throughout a watershed (an area where all water drains across the landscape to one common point) is crucial to minimize drought impacts. In coastal areas, small wetlands can reduce saltwater intrusion through groundwater recharge which helps protect freshwater wetlands from negative impacts such as tree mortality that may result from increased salinity levels by maintaining the water table levels at about sea level.20 Protecting coastal freshwater wetlands reduces flood damages from storm surge.

Water Quality Benefits

A common misconception is that small wetlands are isolated and therefore do not provide important hydrological and water quality benefits. All wetlands, small and large, are part of the larger surrounding watershed and can influence other ecosystems within the watershed. Evapotranspiration is an important ecosystem service provided by small wetlands that stabilizes the health of the surrounding watershed by reducing excess stormwater runoff that can carry harmful contaminants, excess nutrients, and sediment that impair water quality (Figure 3). For example, when analyzing the same rainfall event, “one inch of rain on an acre of woods produces little to no stormwater runoff” while “one inch of rain on an acre of asphalt produces 27,000 gallons of stormwater runoff that contains a variety of pollutants and causes widespread erosion.”22 Small wetland vegetation and microtopography on the soil surface improve water quality by slowing the movement of water downslope and allowing for sediment to settle out, bacteria to breakdown contaminants, and excess nutrients to be taken up by plants and microorganisms, thus improving water quality. The wetland’s “natural filtration process makes water cleaner for drinking, swimming, and provides habitat for plants and animals.”19

Figure 3. How wetlands work and their role in water quality and ecosystem health (23).

Recreational Benefits

In 2016, 103.7 million Americans spent $156.9 billion participating in recreational activities such as hunting; fishing; and observing, feeding, and photographing wildlife in natural areas (Figure 4).24 The 2011 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation report for North Carolina showed a total of $3.3 billion was spent on recreational activities related to wildlife that included $525 million for hunting, $1.5 billion spent for fishing, and $930 million spent for wildlife-watching.25 People visiting small wetlands to hunt, fish, and observe wildlife can boost local economies, especially in rural areas, by spending money on and requiring services for transportation, lodging, food, beverages, equipment, licenses, permits, memberships, and/or land leases.

Figure 4. Wildlife-dependent recreational activities (26).

In a public input survey conducted in 2014 by the North Carolina Division of Parks and Recreation (DPR), most respondents (81%) believe it is “extremely or somewhat important to spend public funds to acquire land and develop outdoor state parks and recreation areas in North Carolina” but many indicated that a lack of time (59%) or a lack of available facilities (23%) are barriers to their participation in outdoor recreation.27 Preserving small wetlands and adding amenities such as walking trails in urban and residential areas makes outdoor recreation activities more accessible. This would also improve nearby property values and promote healthier lifestyles, including physical and mental health.28 The economic benefit gained from recreational activities heavily depends on the presence and health of local wetlands.

Biodiversity Benefits

Wetlands host a variety of plant and animal species, including approximately 70% of rare or endangered species in North Carolina that require wetlands to survive.29 In the Mountains and western Piedmont, small wetlands provide habitat for over 90 rare, threatened, or endangered plant and animal species.30 Mountain bogs are typically small and are among the rarest, most vulnerable habitats in the United States. These wetlands are the only or primary habitat for wildlife species such as the southern bog lemming (Synaptomys cooperi), a type of small mammal, the bog turtle (Glyptemys muhlenbergii), and plants species including swamp pink (Helonias bullata), mountain sweet pitcher plant (Sarracenia rubra), and bunched arrowhead (Sagittaria fasciculata).30,12 Without mountain bogs, these species, along with many others, would not be able to survive. These species are adapted to wetlands without the high velocities of water that stream floodplain wetlands experience.

On January 13, 2022, the Center for Biological Diversity filed a petition to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) “to protect the southern population of the bog turtle as a federal endangered species in Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Georgia” and request the establishment of designated critical habitat.32 There are currently only 10 sites with viable bog turtle populations (at least 40 individuals) in North Carolina.32 Almost all the individuals found at these sites were adults, meaning there are very few young turtles to replace the adults and continue the survival of the species.32 By listing the bog turtle as a federal endangered species and designating critical habitat, protection would be provided under the Endangered Species Act for mountain bogs that are used by existing populations.

Photo: The Appalachian Voice. 2014 (31).

Small wetland habitats across North Carolina are also critical breeding grounds for amphibian and crayfish species because they often do not contain fish predators that may be present in larger, more permanently flooded water bodies.[33] In North Carolina, small wetlands are habitat to approximately 20 species of salamanders, including two state-listed threatened species [Eastern tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum tigrinum) and Mabee’s salamander (Ambystoma mabeei)] and three state-listed species of special concern [dwarf salamander (Eurycea quadridigitata), four-toed salamander (Hemidactylium scutatum), and mole salamander (Ambystoma talpoideum)].[33, 34, 35, 36] There are also many species of frogs and toads in North Carolina that use small wetlands as habitat and breeding grounds, including two state-listed endangered species [Carolina gopher frog (Rana capito) and ornate chorus frog (Pseudacris ornata)], one state-listed threatened species [pine barrens treefrog (Hyla andersonii)], and one state-listed species of special concern [northern gray treefrog (Hyla versicolor)]. [33, 34, 35, 36]

Small wetlands tend to attract wading birds, waterfowl, and songbirds since they are prime nesting and feeding areas.[33] Many migratory birds such as egrets, falcons, hawks, herons, waterfowl, and vultures depend on wetlands during their migration and breeding seasons.[37] Small wetlands host a variety of invertebrates and insects that are an excellent food source for birds and other wildlife.[20] All animals require drinking water for survival; therefore, small wetlands are an important clean water drinking source for wildlife, especially in areas surrounded by uplands where drinking sources may be limited. Many mammals including bats, black bears, bobcats, coyotes, opossums, rabbits, raccoons, skunks, and white-tailed deer utilize both wetland and upland habitats.

The loss and degradation of small wetlands have negative consequences for biodiversity and can lead to the extinction of endangered species. Development can cause a direct loss of wetlands due to filling and draining, but other impacts such as increases in impervious surfaces, accelerated drainage, habitat fragmentation, pollution, decrease in water quality, and the introduction of exotic invasive species all threaten the health and existence of small wetland habitats.

SOLUTION: Protect Small Wetlands

As federal regulations surrounding wetland protection continue to change, it is important that state rules incorporate measures to strengthen regulations to protect small wetlands. During the Trump administration, many wetlands lost federal protection under the Navigable Wetlands Protect Rule (NWPR) that went into effect in June 2020, including small wetlands that were not considered “adjacent wetlands” to jurisdictional waters required by the NWPR. It was estimated approximately 1.3 million acres of wetlands in North Carolina lost federal protection under the NWPR.[38] To meet the federal non-jurisdictional wetland permitting gap that the NWPR created for wetlands that were not isolated but no longer met the federal definition of a jurisdictional wetlands, North Carolina passed temporary rules; however, these temporary rules had high permitting thresholds (one acre in the Coastal Plain, one-half acre in the Piedmont, and one-third acre in the Mountains), so many small wetland losses were considered “deemed permitted” and these wetlands were not protected and losses were not reported.[39] North Carolina then started working on permanent rules and proposed lowering the permitting threshold for all non-isolated wetlands to one-tenth acre, including those considered federally non-jurisdictional.40 In August 2021, the U.S. District Court for the District of Arizona issued an order vacating and remanding the NWPR resulting in the Waters of the US (WOTUS) pre-2015 rule being reinstated.[41] To address any possible future changes to the federal protection of wetlands, North Carolina is still continuing to pursue the permanent rules that would better protect small wetlands statewide. This will encourage projects to include more rigorous avoidance and minimization measures to reduce costs associated with permitting and mitigation for impacts to wetlands.

While this would be a positive step forward for wetland protection, it should be noted that more than half of wetlands in the Mountains and about half of wetlands in the Piedmont were found to be less than one-tenth acre in recent studies conducted by the DWR (Figure 2), which means some of these wetlands can be lost without permitting requirements if total impacts for a project are less than one-tenth acre.[5] Permitting thresholds for impacts to isolated wetlands, such as mountain bogs and basin wetlands, are higher than one-tenth acre: one acre in the Coastal Plain, one-half acre in the Piedmont, and one-third of an acre in the Mountains.[42] While isolated wetlands do not have a direct surface connection to relatively permanent waters, they still perform functions that are important for the overall health of a watershed, wildlife, and humans. Because the size of a wetland is not a direct indicator of how well it is functioning or the value it has to the surrounding ecosystem, other criteria such as wetland density, position, and ecological value within a watershed, need to be incorporated into wetland regulations.1 A landscape approach to regulate wetlands can be used to avoid and minimize impacts to wetlands that are in positions that provide the most environmental, economic, and community benefits. An updated, accurate map of wetlands in North Carolina would provide a greater level of understanding for where small wetlands occur, better inform wetland regulations, and potentially streamline the environmental permitting process. [5]

Conclusions

Small wetlands offer considerable benefits to North Carolina through environmental and economic services. Small wetlands provide flood protection against growing impacts from climate change including stronger storms and increasing heavy downpour events and have been shown to be more efficient at reducing runoff than larger wetlands and are a main source of water and sediment filtration that improves water quality. Small wetlands provide habitat for rare, threatened, and endangered species; therefore, their protection is imperative in the face of growing extinction events. Small wetlands serve as critical breeding grounds for amphibian species and are necessary feeding and drinking sources for wildlife. They support recreational opportunities and stimulate the economy.

Photo: Walter Magazine. 2019. Exploring the Walnut Creek Wetland Center. Photography by Justin Kase Conder (41).

The importance of small wetlands warrants their protection. Because federal wetland regulations fluctuate over time and use size as the primary requirement for permitting, the state of North Carolina should develop and maintain regulations that give protection to small wetlands based on their abundance and position in the watershed, beneficial services, and ecological importance.

About the Author

Amanda Johnson is a Professional Wetland Scientist who works as an environmental scientist. She has been a volunteer with Carolina Wetlands Association since 2019 where she serves as the Project Manager for the North Carolina Pilot Volunteer Wetlands Monitoring Program and is a member of the Science Committee. In her free time, she enjoys spending time with her family, dog, and cat.

References

- Snodgrass, Joel W., et al. (2001). Relationships among Isolated Wetland Size, Hydroperiod, and Amphibian Species Richness: Implications for Wetland Regulations. Conservation Biology, vol. 14, no. 2, 24, pp. 414–419. https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.99161.x. (Accessed July 16, 2021).

- Natural Resource Conservation Service (NCRS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). (n/d). Wetlands. https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/main/national /water/wetlands/. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- NRCS, USDA. (1995). Wetland Values and Trends. RA Issue Brief #4. nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/nc/home/?cid=stelprdb1042133. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- Richardson, C.J. (2003). Pocosins: Hydrologically isolated or integrated wetlands on the landscape?. Wetlands 23, 563–576. https://doi.org/10.1672/0277-5212(2003)023[0563:PHIOIW]2.0.CO;2. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- Gale, S. (2021). National Wetlands Inventory (NWI) Accuracy in North Carolina. Division of Water Resources (DWR), North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (NCDEQ). https://www.ncwetlands.org/wp-content/uploads/NWI_Accuracy_In_NC_NCDWR-Final_Report_8-10-2021.pdf. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- The Nature Conservancy. (n/d). Stories in North Carolina: Southern Appalachian Mountain Bogs. https://www.nature.org/en-us/about-us/where-we-work/united-states/north-carolina/stories-in-north-carolina/mountain-bogs/. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- Sharitz, R.R. (2003). Carolina bay wetlands: Unique habitats of the southeastern United States. Wetlands 23, 550–562. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1672/0277-5212(2003)023%5b0550:CBWUHO%5d2.0.CO;2. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). (n/d). What is a Wetland? https://www.epa.gov/wetlands/what-wetland. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- (2011). North Carolina Level III Shapefile. https://www.epa.gov/eco-research/ecoregion-download-files-state-region-4. (Accessed December 19, 2021).

- North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission (NCWRC). (2016). 2015 Wildlife Action Plan. https://www.ncwildlife.org/Portals/0/Conserving/documents/2015WildlifeActionPlan/NC-WAP-2015-All-Documents.pdf. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). (2019). National Wetlands Inventory North Carolina Shapefile. https://www.fws.gov/node/264847. (Accessed October 8, 2021).

- DWR, NCDEQ. (2021a). North Carolina Wetlands Information. Water Sciences Section. https://www.ncwetlands.org. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- DWR, NCDEQ. (2021b). North Carolina Wetlands Information. Water Sciences Section. Accuracy of National Wetland Inventory (NWI) Maps in North Carolina. https://www.ncwetlands.org/project/nwi_accuracy/

- NC Wetland Functional Assessment Team. 2016. NC Wetland Assessment Method (NC WAM) User Manual Version 5. https://files.nc.gov/ncdeq/Water%20Quality/Environmental%20Sciences/ECO/Wetlands/NC%20WAM%20User%20Manual%20v5.pdf. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- Carolina Wetlands Association. (2020). Wetlands and Climate Change. http://carolinawetlands.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/WetlandsClimateChange_WhitePaper-Final-Dec2020.pdf. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- Gallup, J. (2021). Quickbait: Hurricane Season. INDY WEEK. https://indyweek.com/news/northcarolina/quickbait-hurricane-season/. (Accessed December 30, 2021).

- Inflation Tool. (2021). Inflation calculator – US Dollar. https://www.inflationtool.com/us-dollar?amount=500000&year1=1970&year2=2021&frequency=yearly. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- Kunkel, K.E., D.R. Easterling, A. Ballinger, S. Bililign, S.M. Champion, D.R. Corbett, K.D. Dello, J. P. Dissen, G.M. Lackmann, R.A. Luettich, Jr., L.B. Perry, W.A. Robinson, L.E. Stevens, B.C. Stewart, and A.J. Terando. (2020). North Carolina Climate Science Report. North Carolina Institute for Climate Studies. https://ncics.org/nccsr. (Accessed January 17, 2022).

- (2006). Economic Benefits of Wetlands. Office of Water. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-02/documents/economicbenefits.pdf. (December 30, 2021).

- Braun, D. G., and V. C. Clark. (2017). The Benefits of Small Wetlands. https://theguardiansofmartincounty.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/BenefitsofSmallWetlands.pdf. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- Ushe, Naledi. (2021). 2 Dead, at Least 35 Missing as Homes ‘Are Completely Destroyed’ in North Carolina. https://people.com/human-interest/2-dead-at-least-35-missing-and-homes-are-completely-destroyed-in-north-carolina-floods/. (Accessed January 17, 2022).

- City of Charlotte. (n/d). Stormwater & Pollution of Streams and Lakes. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Storm Water Services. https://charlottenc.gov/StormWater/SurfaceWaterQuality/Pages/StormwaterandPollutionofStreamsandLakes.aspx. (Accessed January 17, 2022).

- Kanabec SWCD. (n/d). Wetlands. http://www.kanabecswcd.org/wetlands/. (December 30, 2021).

- (2016). Quick Facts from the 2016 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting and Wildlife-Associated Recreation. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/visualizations/2016/demo/fhw16-qkfact.pdf. (Accessed December 30, 2021).

- (2013). Survey Identifies Value of Hunting and Fishing to N.C. Economy. https://www.ncwildlife.org/News/survey-identifies-value-of-hunting-and-fishing-to-nc-economy. (Accessed on December 30, 2021).

- (2016). 2016 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting and Wildlife-Associated Recreation. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/visualizations/2016/demo/fhw16-qkfact.pdf. (Accessed December 30, 2021).

- Division of Parks and Recreation, North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources. (2020). North Carolina Outdoor Recreation Plan 2020-2025. https://files.nc.gov/ncparks/north-carolina-statewide-comprehensive-outdoor-recreation-plan-2020.pdf. (Accessed December 30, 2021).

- Miracle Recreation. (n/d). Benefits of Parks in Your Community. https://www.miracle-recreation.com/blog/benefits-of-parks-in-your-community/. (Accessed December 30, 2021).

- Bales, Jerad D, and Douglas J Newcomb. (1996.) North Carolina Wetland Resources. National Water Summary on Wetland Resources. https://www.fws.gov/wetlands/data/Water-Summary-Reports/National-Water-Summary-Wetland-Resources-North-Carolina.pdf. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- (n/d). Mountain Bogs. https://www.fws.gov/southeast/pubs/mtbog.pdf. (Accessed December 30, 2021).

- Ellis, Amber. (2014). Exploring Mountain Bogs. The Appalachian Voice. https://appvoices.org/2014/08/10/exploring-mountain-bogs/. (Accessed April 12, 2022).

- Center for Biological Diversity. (2022). Petition to List the Southern Population of the Bog Turtle (Glyptemys muhlenbergii) Under the Endangered Species Act as an Endangered or Threatened Species and to Concurrently Designate Critical Habitat. https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/s3-wagtail.biolgicaldiversity.org/documents/Bog-Turtle-Southern-Population-Petition.pdf. (January 31, 2022).

- (2004). Piedmont Small Wetland Communities, Piedmont Ecoregion. https://www.wrcuatweb.org/Portals/0/Conserving/documents/Piedmont/P_Small_wetland_communities.pdf?ver=A2CJzJbrPhmWtjX-0W009Q%3d%3d. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- (2004). Small Wetland Communities, Mid-Atlantic Coastal Plain. https://www.ncwildlife.org/Portals/0/Conserving/documents/Coast/CP_Small_wetland_communities.pdf?ver=rhHkfWCDWhPlB1iPmQganw%3d%3d. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- National Park Service. (n/d). Blue Ridge Amphibian and Reptile Checklist. https://www.nps.gov/blri/learn/nature/upload/BLRI-Herps-Checklist-cb-edits.pdf. (Accessed April 11, 2022).

- (2021). Protected Wildlife Species of North Carolina. https://www.ncwildlife.org/Portals/0/Conserving/documents/Protected-Wildlife-Species-of-NC.pdf. (Accessed April 11, 2022).

- Stewart, Robert E. Jr. (2016). Technical Aspects of Wetlands, Wetlands as Bird Habitat. National Water Summary on Wetland Resources. https://water.usgs.gov/nwsum/WSP2425/birdhabitat.html. (Accessed April 11, 2022).

- DWR, NCDEQ. (2021). Regulatory Impact Analysis: Reinstating Permitting Mechanism for Non-Jurisdictional Wetlands and Waters. https://edocs.deq.nc.gov/WaterResources/DocView.aspx?id=2051205&dbid=0&repo=WaterResources. (Accessed January 31, 2022).

- Discharges to Federally Non-Jurisdictional Wetlands and Federally Non-Jurisdictional Classified Surface Waters. 15A NCAC 02H. 1401-.1405 and .1301. Temporary Rules. (2021). https://edocs.deq.nc.gov/WaterResources/DocView.aspx?id=1898665&dbid=0&repo=WaterResources&cr=1. (Accessed January 31, 2022).

- Discharges to Federally Non-Jurisdictional Wetlands and Federally Non-Jurisdictional Classified Surface Waters. 15A NCAC 02H. 1401-.1405 and .1301. Proposed Permanent Rules. (2021). https://edocs.deq.nc.gov/WaterResources/DocView.aspx?id=2051206& dbid=0&repo=WaterResources. (Accessed January 31, 2022).

- The National Law Review. (2021). Uncertainty Over ‘Waters of the U.S.’ Definition Continues, as Federal Court in Arizona Vacates 2020 Rule. https://www.natlawreview.com/article/uncertainty-over-waters-us-definition-continues-federal-court-arizona-vacates-2020. (Accessed April 11, 2022).

- Isolated Wetlands and Waters (non-404) Rules. 15A NCAC 02H.1305. (2021). https://edocs.deq.nc.gov/WaterResources/DocView.aspx?id=2051206& dbid=0&repo=WaterResources. (Accessed January 31, 2022).

- Walter Magazine. (2019). Exploring the Walnut Creek Wetland Center. https://waltermagazine.wpengine.com/explore/slideshow-walnut-creek-wetland-center/. (Accessed December 30, 2021).

Small wetland habitats across North Carolina are also critical breeding grounds for amphibian and crayfish species because they often do not contain fish predators that may be present in larger, more permanently flooded water bodies.33 In North Carolina, small wetlands are habitat to approximately 20 species of salamanders, including two state-listed threatened species [Eastern tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum tigrinum) and Mabee’s salamander (Ambystoma mabeei)] and three state-listed species of special concern [dwarf salamander (Eurycea quadridigitata), four-toed salamander (Hemidactylium scutatum), and mole salamander (Ambystoma talpoideum)].33, 34, 35, 36 There are also many species of frogs and toads in North Carolina that use small wetlands as habitat and breeding grounds, including two state-listed endangered species [Carolina gopher frog (Rana capito) and ornate chorus frog (Pseudacris ornata)], one state-listed threatened species [pine barrens treefrog (Hyla andersonii)], and one state-listed species of special concern [northern gray treefrog (Hyla versicolor)]. 33, 34, 35, 36

Small wetlands tend to attract wading birds, waterfowl, and songbirds since they are prime nesting and feeding areas.33 Many migratory birds such as egrets, falcons, hawks, herons, waterfowl, and vultures depend on wetlands during their migration and breeding seasons.37 Small wetlands host a variety of invertebrates and insects that are an excellent food source for birds and other wildlife.20 All animals require drinking water for survival; therefore, small wetlands are an important clean water drinking source for wildlife, especially in areas surrounded by uplands where drinking sources may be limited. Many mammals including bats, black bears, bobcats, coyotes, opossums, rabbits, raccoons, skunks, and white-tailed deer utilize both wetland and upland habitats.

The loss and degradation of small wetlands have negative consequences for biodiversity and can lead to the extinction of endangered species. Development can cause a direct loss of wetlands due to filling and draining, but other impacts such as increases in impervious surfaces, accelerated drainage, habitat fragmentation, pollution, decrease in water quality, and the introduction of exotic invasive species all threaten the health and existence of small wetland habitats.

SOLUTION: Protect Small Wetlands

As federal regulations surrounding wetland protection continue to change, it is important that state rules incorporate measures to strengthen regulations to protect small wetlands. During the Trump administration, many wetlands lost federal protection under the Navigable Wetlands Protect Rule (NWPR) that went into effect in June 2020, including small wetlands that were not considered “adjacent wetlands” to jurisdictional waters required by the NWPR. It was estimated approximately 1.3 million acres of wetlands in North Carolina lost federal protection under the NWPR.38 To meet the federal non-jurisdictional wetland permitting gap that the NWPR created for wetlands that were not isolated but no longer met the federal definition of a jurisdictional wetlands, North Carolina passed temporary rules; however, these temporary rules had high permitting thresholds (one acre in the Coastal Plain, one-half acre in the Piedmont, and one-third acre in the Mountains), so many small wetland losses were considered “deemed permitted” and these wetlands were not protected and losses were not reported.39 North Carolina then started working on permanent rules and proposed lowering the permitting threshold for all non-isolated wetlands to one-tenth acre, including those considered federally non-jurisdictional.40 In August 2021, the U.S. District Court for the District of Arizona issued an order vacating and remanding the NWPR resulting in the Waters of the US (WOTUS) pre-2015 rule being reinstated.41 To address any possible future changes to the federal protection of wetlands, North Carolina is still continuing to pursue the permanent rules that would better protect small wetlands statewide. This will encourage projects to include more rigorous avoidance and minimization measures to reduce costs associated with permitting and mitigation for impacts to wetlands.

While this would be a positive step forward for wetland protection, it should be noted that more than half of wetlands in the Mountains and about half of wetlands in the Piedmont were found to be less than one-tenth acre in recent studies conducted by the DWR (Figure 2), which means some of these wetlands can be lost without permitting requirements if total impacts for a project are less than one-tenth acre.5 Permitting thresholds for impacts to isolated wetlands, such as mountain bogs and basin wetlands, are higher than one-tenth acre: one acre in the Coastal Plain, one-half acre in the Piedmont, and one-third of an acre in the Mountains.42 While isolated wetlands do not have a direct surface connection to relatively permanent waters, they still perform functions that are important for the overall health of a watershed, wildlife, and humans. Because the size of a wetland is not a direct indicator of how well it is functioning or the value it has to the surrounding ecosystem, other criteria such as wetland density, position, and ecological value within a watershed, need to be incorporated into wetland regulations.1 A landscape approach to regulate wetlands can be used to avoid and minimize impacts to wetlands that are in positions that provide the most environmental, economic, and community benefits. An updated, accurate map of wetlands in North Carolina would provide a greater level of understanding for where small wetlands occur, better inform wetland regulations, and potentially streamline the environmental permitting process. 5

Conclusions

Small wetlands offer considerable benefits to North Carolina through environmental and economic services. Small wetlands provide flood protection against growing impacts from climate change including stronger storms and increasing heavy downpour events and have been shown to be more efficient at reducing runoff than larger wetlands and are a main source of water and sediment filtration that improves water quality. Small wetlands provide habitat for rare, threatened, and endangered species; therefore, their protection is imperative in the face of growing extinction events. Small wetlands serve as critical breeding grounds for amphibian species and are necessary feeding and drinking sources for wildlife. They support recreational opportunities and stimulate the economy.

Photo: Walter Magazine. 2019. Exploring the Walnut Creek Wetland Center. Photography by Justin Kase Conder (41).

The importance of small wetlands warrants their protection. Because federal wetland regulations fluctuate over time and use size as the primary requirement for permitting, the state of North Carolina should develop and maintain regulations that give protection to small wetlands based on their abundance and position in the watershed, beneficial services, and ecological importance.

About the Author

Amanda Johnson is a Professional Wetland Scientist who works as an environmental scientist. She has been a volunteer with Carolina Wetlands Association since 2019 where she serves as the Project Manager for the North Carolina Pilot Volunteer Wetlands Monitoring Program and is a member of the Science Committee. In her free time, she enjoys spending time with her family, dog, and cat.

References

- Snodgrass, Joel W., et al. (2001). Relationships among Isolated Wetland Size, Hydroperiod, and Amphibian Species Richness: Implications for Wetland Regulations. Conservation Biology, vol. 14, no. 2, 24, pp. 414–419. https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.99161.x. (Accessed July 16, 2021).

- Natural Resource Conservation Service (NCRS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). (n/d). Wetlands. https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/main/national /water/wetlands/. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- NRCS, USDA. (1995). Wetland Values and Trends. RA Issue Brief #4. nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/nc/home/?cid=stelprdb1042133. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- Richardson, C.J. (2003). Pocosins: Hydrologically isolated or integrated wetlands on the landscape?. Wetlands 23, 563–576. https://doi.org/10.1672/0277-5212(2003)023[0563:PHIOIW]2.0.CO;2. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- Gale, S. (2021). National Wetlands Inventory (NWI) Accuracy in North Carolina. Division of Water Resources (DWR), North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (NCDEQ). https://www.ncwetlands.org/wp-content/uploads/NWI_Accuracy_In_NC_NCDWR-Final_Report_8-10-2021.pdf. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- The Nature Conservancy. (n/d). Stories in North Carolina: Southern Appalachian Mountain Bogs. https://www.nature.org/en-us/about-us/where-we-work/united-states/north-carolina/stories-in-north-carolina/mountain-bogs/. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- Sharitz, R.R. (2003). Carolina bay wetlands: Unique habitats of the southeastern United States. Wetlands 23, 550–562. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1672/0277-5212(2003)023%5b0550:CBWUHO%5d2.0.CO;2. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). (n/d). What is a Wetland? https://www.epa.gov/wetlands/what-wetland. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- (2011). North Carolina Level III Shapefile. https://www.epa.gov/eco-research/ecoregion-download-files-state-region-4. (Accessed December 19, 2021).

- North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission (NCWRC). (2016). 2015 Wildlife Action Plan. https://www.ncwildlife.org/Portals/0/Conserving/documents/2015WildlifeActionPlan/NC-WAP-2015-All-Documents.pdf. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). (2019). National Wetlands Inventory North Carolina Shapefile. https://www.fws.gov/node/264847. (Accessed October 8, 2021).

- DWR, NCDEQ. (2021a). North Carolina Wetlands Information. Water Sciences Section. https://www.ncwetlands.org. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- DWR, NCDEQ. (2021b). North Carolina Wetlands Information. Water Sciences Section. Accuracy of National Wetland Inventory (NWI) Maps in North Carolina. https://www.ncwetlands.org/project/nwi_accuracy/

- NC Wetland Functional Assessment Team. 2016. NC Wetland Assessment Method (NC WAM) User Manual Version 5. https://files.nc.gov/ncdeq/Water%20Quality/Environmental%20Sciences/ECO/Wetlands/NC%20WAM%20User%20Manual%20v5.pdf. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- Carolina Wetlands Association. (2020). Wetlands and Climate Change. http://carolinawetlands.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/WetlandsClimateChange_WhitePaper-Final-Dec2020.pdf. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- Gallup, J. (2021). Quickbait: Hurricane Season. INDY WEEK. https://indyweek.com/news/northcarolina/quickbait-hurricane-season/. (Accessed December 30, 2021).

- Inflation Tool. (2021). Inflation calculator – US Dollar. https://www.inflationtool.com/us-dollar?amount=500000&year1=1970&year2=2021&frequency=yearly. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- Kunkel, K.E., D.R. Easterling, A. Ballinger, S. Bililign, S.M. Champion, D.R. Corbett, K.D. Dello, J. P. Dissen, G.M. Lackmann, R.A. Luettich, Jr., L.B. Perry, W.A. Robinson, L.E. Stevens, B.C. Stewart, and A.J. Terando. (2020). North Carolina Climate Science Report. North Carolina Institute for Climate Studies. https://ncics.org/nccsr. (Accessed January 17, 2022).

- (2006). Economic Benefits of Wetlands. Office of Water. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-02/documents/economicbenefits.pdf. (December 30, 2021).

- Braun, D. G., and V. C. Clark. (2017). The Benefits of Small Wetlands. https://theguardiansofmartincounty.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/BenefitsofSmallWetlands.pdf. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- Ushe, Naledi. (2021). 2 Dead, at Least 35 Missing as Homes ‘Are Completely Destroyed’ in North Carolina. https://people.com/human-interest/2-dead-at-least-35-missing-and-homes-are-completely-destroyed-in-north-carolina-floods/. (Accessed January 17, 2022).

- City of Charlotte. (n/d). Stormwater & Pollution of Streams and Lakes. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Storm Water Services. https://charlottenc.gov/StormWater/SurfaceWaterQuality/Pages/StormwaterandPollutionofStreamsandLakes.aspx. (Accessed January 17, 2022).

- Kanabec SWCD. (n/d). Wetlands. http://www.kanabecswcd.org/wetlands/. (December 30, 2021).

- (2016). Quick Facts from the 2016 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting and Wildlife-Associated Recreation. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/visualizations/2016/demo/fhw16-qkfact.pdf. (Accessed December 30, 2021).

- (2013). Survey Identifies Value of Hunting and Fishing to N.C. Economy. https://www.ncwildlife.org/News/survey-identifies-value-of-hunting-and-fishing-to-nc-economy. (Accessed on December 30, 2021).

- (2016). 2016 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting and Wildlife-Associated Recreation. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/visualizations/2016/demo/fhw16-qkfact.pdf. (Accessed December 30, 2021).

- Division of Parks and Recreation, North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources. (2020). North Carolina Outdoor Recreation Plan 2020-2025. https://files.nc.gov/ncparks/north-carolina-statewide-comprehensive-outdoor-recreation-plan-2020.pdf. (Accessed December 30, 2021).

- Miracle Recreation. (n/d). Benefits of Parks in Your Community. https://www.miracle-recreation.com/blog/benefits-of-parks-in-your-community/. (Accessed December 30, 2021).

- Bales, Jerad D, and Douglas J Newcomb. (1996.) North Carolina Wetland Resources. National Water Summary on Wetland Resources. https://www.fws.gov/wetlands/data/Water-Summary-Reports/National-Water-Summary-Wetland-Resources-North-Carolina.pdf. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- (n/d). Mountain Bogs. https://www.fws.gov/southeast/pubs/mtbog.pdf. (Accessed December 30, 2021).

- Ellis, Amber. (2014). Exploring Mountain Bogs. The Appalachian Voice. https://appvoices.org/2014/08/10/exploring-mountain-bogs/. (Accessed April 12, 2022).

- Center for Biological Diversity. (2022). Petition to List the Southern Population of the Bog Turtle (Glyptemys muhlenbergii) Under the Endangered Species Act as an Endangered or Threatened Species and to Concurrently Designate Critical Habitat. https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/s3-wagtail.biolgicaldiversity.org/documents/Bog-Turtle-Southern-Population-Petition.pdf. (January 31, 2022).

- (2004). Piedmont Small Wetland Communities, Piedmont Ecoregion. https://www.wrcuatweb.org/Portals/0/Conserving/documents/Piedmont/P_Small_wetland_communities.pdf?ver=A2CJzJbrPhmWtjX-0W009Q%3d%3d. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- (2004). Small Wetland Communities, Mid-Atlantic Coastal Plain. https://www.ncwildlife.org/Portals/0/Conserving/documents/Coast/CP_Small_wetland_communities.pdf?ver=rhHkfWCDWhPlB1iPmQganw%3d%3d. (Accessed February 1, 2022).

- National Park Service. (n/d). Blue Ridge Amphibian and Reptile Checklist. https://www.nps.gov/blri/learn/nature/upload/BLRI-Herps-Checklist-cb-edits.pdf. (Accessed April 11, 2022).

- (2021). Protected Wildlife Species of North Carolina. https://www.ncwildlife.org/Portals/0/Conserving/documents/Protected-Wildlife-Species-of-NC.pdf. (Accessed April 11, 2022).

- Stewart, Robert E. Jr. (2016). Technical Aspects of Wetlands, Wetlands as Bird Habitat. National Water Summary on Wetland Resources. https://water.usgs.gov/nwsum/WSP2425/birdhabitat.html. (Accessed April 11, 2022).

- DWR, NCDEQ. (2021). Regulatory Impact Analysis: Reinstating Permitting Mechanism for Non-Jurisdictional Wetlands and Waters. https://edocs.deq.nc.gov/WaterResources/DocView.aspx?id=2051205&dbid=0&repo=WaterResources. (Accessed January 31, 2022).

- Discharges to Federally Non-Jurisdictional Wetlands and Federally Non-Jurisdictional Classified Surface Waters. 15A NCAC 02H. 1401-.1405 and .1301. Temporary Rules. (2021). https://edocs.deq.nc.gov/WaterResources/DocView.aspx?id=1898665&dbid=0&repo=WaterResources&cr=1. (Accessed January 31, 2022).

- Discharges to Federally Non-Jurisdictional Wetlands and Federally Non-Jurisdictional Classified Surface Waters. 15A NCAC 02H. 1401-.1405 and .1301. Proposed Permanent Rules. (2021). https://edocs.deq.nc.gov/WaterResources/DocView.aspx?id=2051206& dbid=0&repo=WaterResources. (Accessed January 31, 2022).

- The National Law Review. (2021). Uncertainty Over ‘Waters of the U.S.’ Definition Continues, as Federal Court in Arizona Vacates 2020 Rule. https://www.natlawreview.com/article/uncertainty-over-waters-us-definition-continues-federal-court-arizona-vacates-2020. (Accessed April 11, 2022).

- Isolated Wetlands and Waters (non-404) Rules. 15A NCAC 02H.1305. (2021). https://edocs.deq.nc.gov/WaterResources/DocView.aspx?id=2051206& dbid=0&repo=WaterResources. (Accessed January 31, 2022).

- Walter Magazine. (2019). Exploring the Walnut Creek Wetland Center. https://waltermagazine.wpengine.com/explore/slideshow-walnut-creek-wetland-center/. (Accessed December 30, 2021).